|

Question: My Finnish teacher and my friends keep telling me that I should stop translating everything from English to Finnish and start thinking in Finnish instead. I have no clue how to do that. How do I start thinking in another language? My answer: This is an area of language learning that I find fascinating, thank you for the great question! In this post, I’ll share what works for me as a language learner, and what many of my students have also found helpful. Thinking practice. Set a timer for 5 minutes and do your best to think in Finnish for that period of time. You will, inevitably, think in other languages as well, but any time you notice it bring yourself back to the effort of thinking in Finnish. At first, it may be that you aren't able to think in Finnish at all, but when you keep going, you'll start to notice it getting easier and easier. However, a caveat with this one: not everyone has an inner monologue where they “speak” a specific language in their head, in which case I recommend the next technique. Talking to yourself. Another really helpful technique is to talk to yourself out loud in Finnish for a set period of time. Even one minute a day, five days a week, does wonders. If you want to speak with any fluency, you can’t do a lot of translating, so talking out loud almost forces you to start thinking in Finnish. Talking to others. No matter how difficult this may seem at first, start speaking Finnish in real life situations, even if it's just a few words a day. Remember that there's no shame in having to switch to another language when you need to, but try to stick to Finnish as best you can. Reading in Finnish. Regular reading in Finnish has the benefit of almost automatically switching your thoughts to Finnish. I recommend you start with a selkokirja, a novel in easy Finnish. My personal favorite is Yösyöttö by Eve Hietamies (original novel) and Hanna Männikkölahti (easy Finnish adaptation). Another great option is following the news in easy Finnish. All of these techniques work best if you can build them into your daily routine. I’m trying to get better at speaking French, so I spend the walking or biking distance between my child’s daycare and my office either thinking in French or speaking it out loud. I avoid weird looks by having my headphones on, so it looks like I’m talking on the phone or taking a Zoom call (or, if I’m feeling confident, I’ll ditch the headphones and embrace the weird looks). I also know many French people living in Helsinki who are kind enough to want to speak French with me, so I also do my best to speak French every week. Readers, what’s your experience? How did you make the switch from translating to thinking in Finnish? Were you able to start thinking in Finnish right at the start of your learning journey, or was it a process that took some time? What worked for you? Picture by Finmiki

Today, I’ll be answering two questions on the same topic. Here both questions first:

Enitan writes: Hei Mari, how are you today? Could you help with a link that gives a distinct explanation on akkusatiivi and genetiivi? I've searched through your blog but couldn't find anything related to it. Thanks Sigrid writes: Moi! Onko akkusatiivi vielä suomenkielessä? Mulla on ikivanha suomen-norja oppikirja, ja siellä on akkuusatiivi, mutta uusissa kirjoissa se on pikemminkin genitiivi, vaikka se on erilainen (genetiivi yksikössä ja nominatiivi monikossa, ja persoonapronominit ovat myös erilaisia). Toivottavasti ymmärrät mitä tarkoitan! My translation: Hi! Is the accusative still in the Finnish language? I have a very old Finnish-Norwegian textbook, and they talk about the accusative, but new textbooks will rather talk about the genitive, though it’s differen (genitive in the singular and nominative in the plural, and personal pronouns are also different) I hope you understand what I mean! My answer: Hi Enitan and Sigrid, thanks for the great questions! There's a bit of a terminology issue here, as akkusatiivi or accusative can mean different things. As Sigrid noticed, older and newer books use different words to talk about the object. In most modern grammars, akkusatiivi means the object forms of the personal pronouns: Näin sinut eilen. I saw you yesterday. sinut = akkusatiivi of the word sinä The corresponding question word is also in the accusative form: Kenet näit eilen? Who(m) did you see yesterday? kenet = akkusatiivi of the word kuka In every other type of word, the same form is the genitive case: Näin Marin eilen. I saw Mari yesterday. Mari is in the genitive case, which tells us that Mari is the object of the sentence, the person being seen. However, in older grammars, they usually refer to the form Marin as akkusatiivi as well, which is pretty confusing. And also nominative objects might be called accusatives. In modern grammars, there are two types of objects: 1. Partitive objects (partitiiviobjekti). These are always in the partitive case. Juon kahvia. I’m drinking coffee or some coffee. Minun täytyy juoda kahvia. I have to drink coffee or some coffee. 2. Total objects (totaaliobjekti). These can be in the genitive, nominative or accusative case. 2.1 Genitive (genetiivi): Juon kahvin. I’m drinking a coffee (I have a defined amount and I’m drinking all of it). 2.2 Nominative (nominatiivi eli perusmuoto) Minun täytyy juoda kahvi. I have to drink a coffee. 2.3 Accusative Näin heidät eilen. I saw them yesterday. If you speak a language that has something called the aspect, like Slavic langugages or Hungarian, you might find that this sounds familiar. Slavic languages and Hungarian have different verb forms to describe ongoing processes and actions that are over and done with. Finnish expresses the same thing by changing the form of the object. So to recap, the case of the total object is either the genitive or the nominative, or for personal pronouns and their corresponding question words, the accusative (minut, sinut, kenet). In older grammars, these were called accusative objects instead of total objects, and kahvin was said to be in the accusative case. This was confusing because the same word was used for both the case and the phenomenon, and also the accusative case looks exactly like the genitive in modern Finnish, so some linguists decided to make the terminology clearer by starting to talk about total objects instead of accusative objects. However, changing the terminology resulted in even more confusion, because now we have two sets of competing terms flying around. If you’re already familiar with the concept of accusatives, it might be useful to use the old terminology, but if you’re not, I’d say stick with the new terminology. In my classes, I often find myself talking about genetiivi-akkusatiivi to help everyone follow along (though I’m not sure how helpful that monster of a word really is). If you’d like to read about all this in more detail, the wonderful website Uusi kielemme has a very comprehensive article about the object in English. A reader writes: I'm a complete beginner, and my only motivation to study Finnish is to pass the YKI test. I would like some guidance on how to achieve my goal as efficiently as possible, and I don't think regular language course are the way to go. Do you have a specialized YKI curriculum for beginners? My answer: Thank you for the great question, which is something that I get asked quite often, so you’re not alone in wondering this! Unfortunately, I have some bad news for you: there isn't any shortcut to the language skills needed to pass the YKI test. Passing the intermediate YKI is a great and valuable goal, but it’s quite an impossible one to reach without acquiring basic language skills first. If your one and only goal is to pass the intermediate YKI test (the level required for citizenship), you will likely require more time to get to the required level, not less. The YKI test is a highly practical kind of language test. It tests your ability to manage in Finnish in a variety of everyday situations, and the best possible preparation for YKI is using as much Finnish as possible in your everyday life. The required level to pass the YKI test is also quite high (YKI 3 or B1). It's a level that enables you to go about your daily life in Finnish, to read and listen to the news and even to handle more complicated things like banking and taxes in Finnish. If you have Finnish relatives, at B1 you can understand the coffee table conversations their kahvipöytäkeskustelu and participate. You can read novels in easy Finnish without too much of a struggle, you can study at vocational school (if you have support with the language), you can watch the news and television and listen to music and understand what's going on. If your goal is Finnish citizenship, wouldn't you also love to be able to do all these things? Only about third of the Finnish population is fluent in English so you're missing out on a lot if you are only communicating in English. My number one advice for you would be a regular beginner's course in Finnish or private Finnish lessons. A good place to start looking is Finnishcourses.fi, which hosts quite a comprehensive listing of Finnish courses in the Helsinki region and in other big cities as well as online. If you’d prefer to work with a private teacher, check out Hanna’s listing of private Finnish teachers, as well as this simple padlet page which lists courses by small teaching businesses like mine. Once you're at an early intermediate level (late stages of A2 in CEFR speak), I'd love to have you in my YKI preparatory courses, which is to what you're looking for but for intermediate learners: a specifically designed curriculum for students who are aiming for the intermediate YKI test in Finnish. Here’s a blog post to help you figure out if you’re ready. Luckily, as the YKI is such an everyday kind of language test, attending a well designed YKI course will have the added benefit of helping you better your real life language skills as well. Some students of mine also attend my YKI courses just for the general language skills without aiming for YKI, and many also continue the course series after passing the YKI test. I wish you the best of luck on your learning journey with this wonderful language! I'd love to hear from those of you who have already attended a beginner's course. What worked? What didn't? Leave a comment or join the conversation on my Facebook page, LinkedIn or Twitter. Picture by Pexels

Question: All my usual Finnish courses are on a break in July, but I’d like to keep up with my Finnish. Any ideas on how to do that? What a great and timely question! Most schools and training providers are closed in July (including my own small teaching business), but otherwise the summer is a great time to study and practice Finnish. Here are some ideas on how to do that. 1. Speak Finnish in real life situations. I know that this can feel like jumping into the deep end if you’re still at the beginning of your journey (and even later on), but there’s no shame in just using the Finnish you have and then switching to English or another language when you need to. Even if you just know a few words in Finnish, there’s already a lot you can do with just ”Hei, kahvi, kiitos” (look at you ordering a coffee in Finnish just like a native speaker would). If you’re in Finland, there are countless opportunities to speak Finnish in everyday situations: cafés, shops, libraries, the market, museums… The list is endless! You can also find some great opportunities to practice online, like social media (especially groups and pages centered around your interests are great, though a bit more advanced of course). For example, you could join a online bookclub, chat about parenting or join a foraging group. 2. Talk to yourself in Finnish. Out loud or by trying to think in Finnish, at home, in the car, while exercising. Just switching your brain to Finnish (or trying to) once in a while is really beneficial for your overall language skills. Don't worry about making mistakes, the key thing is to practice speaking or thinking in Finnish. 3. Self-study courses. There are some great self-study courses and learning materials that you can use any time, many of them free of chage. For beginners, Superalkeet is great, and Työelämän suomea is excellent if you’re at a more intermediate level. Puhutsä suomee is a good introduction to spoken Finnish and suitable for many levels, depending on how familiar you are with puhekieli. The freely available material Kotisuomessa goes from 0 all the way to B2. Apps like Duolingo, WordDive and Glossika can also be great. This is another list that just goes on and on! 4. Series, books, podcasts, music. These are always a good idea, even alongside a course. Books in easy Finnish are a great idea at level A2 and up, watching tv in Finnish with or without subtitles is great at every level. Listening to podcasts and music in Finnish will help you level up your language skills even if you don’t understand a single word at first. 5. Clubs and language cafés. Many Finnish language clubs and language cafés still continue meeting up in the summer, both online and offline. For example, here are all the events organized by the public libraries in Helsinki, all over the capital city region and online as well. Once you’re at an intermediate level, the topic of the meetup doesn’t have to be about learning Finnish at all – think of what you’re interested in and find out how to do that with others in Finnish. It could be an open university course on a topic you love or a dance class. 7. Attend a course or hire a private teacher. Luckily, not everyone is on a summer break in July. For example, my lovely colleagues Päivi Virkkunen and Liis Viks are available for private lessons all through the summer. Ihanaa kesää!

ihana-partitiivi kesä-partitiivi summer-partitive lovely-partitive = Have a lovely summer! Cindy asks: Hei! Does the yki test require one to write/speak in kirjakieli? or can one use puhekieli? Thx, Cindy Hei Cindy! Thank you for a great question! The answer depends on what level you’re aiming for, so I’ll be covering a few different levels in this blog post. Written and spoken Finnish are quite different, which can be a real challenge when you’re learning Finnish. Standard Written Finnish or kirjakieli (also referred to as yleiskieli) is the form of the Finnish language that you’ll find in the newspaper, in formal messages and when listening to something pre-scripted, like the news or prepared speeches. Puhekieli or spoken Finnish is the form of Finnish that you’ll hear in everyday conversations and also in written form in informal messages, like on a lot of social media and instant messaging. Like any language, Finnish is spoken differently in different social contexts and in different regions. When I talk about puhekieli in this post, I mean what is also known as yleispuhekieli or Standard Spoken Finnish. So what does that mean for the YKI test? YKI level 3 or CEFR level B1 If you’re aiming for a 3, which is the level required for Finnish citizenship, then you don’t have to pay much attention to whether you’re using puhekieli or kirjakieli. At level 3, the main goal is just to make yourself understood, and any version of the Finnish language is fine. What matters more is that you have enough language skills to manage in everyday situations. You don’t have speak or write elegantly and mistakes are very much expected, as long as your writing and speaking can be understood. However, being able to show that you already know some of the differences between puhekieli and kirjakieli definitely won’t hurt. In the speaking test, it’s great If you can use some puhekieli, but just using written forms is also absolutely fine. For example, you might want to say mä for minä (I) and sä for sinä (you), and use the spoken language me-passive: mennään syömään, lähdetään and so forth. Likewise, if you can use kirjakieli for the more formal tasks in the writing exam, that’s great, but the main goal is to just write something in understandable Finnish. At level 3, you should also have a basic understanding of how to write formal and informal messages, for example, the phrases needed to open and finish a message. YKI level 4 or CEFR level B2 At level 4, you should already be able to modify the way you’re speaking and writing according to the situation you’re in. So, for example, at level 4, you might be writing in casual puhekieli to a friend, but a more formal email would be completely in kirjakieli. YKI levels 5 and C or CEFR levels C1 and C2 At levels 5 and 6 (YKI’s ylin taso or highest level), you’re able to really fine tune your lingustic choices to suit the situation you’re in. You can use and understand many different types of language easily and comfortably. In my classes, I usually teach both kirjakieli and puhekieli, as I think that it’s important to know about the different forms and especially to understand both from the start. However, speaking in kirjakieli is absolutely fine, and writing in puhekieli already goes a very very long way. In the YKI test, if you’re aiming for level 3, use whatever you feel most comfortable with. The writing and reading comprehension sections of the YKI test are conducted in a traditional classroom much like this one.

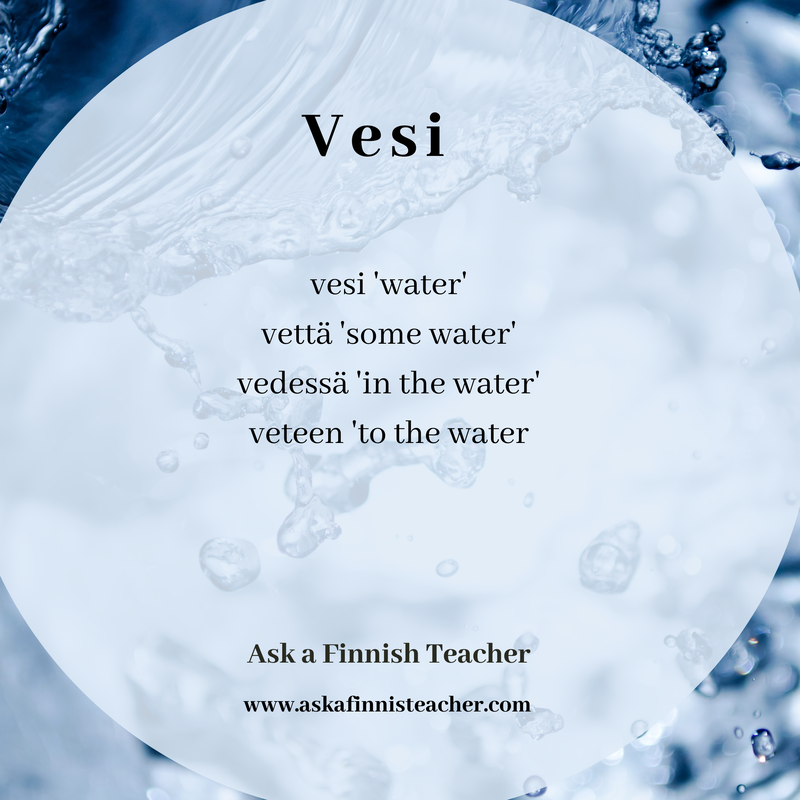

Pictuce by Wokandapix A student asks: Which forms should I learn when I’m learning Finnish words? In my last post, we talked about how to find out what different forms any given Finnish word has. But when someone is speaking to you in Finnish right here and now, you obviously don’t have the luxury of using an online tool to figure out what words they’re using – the forms already need to be in your head so that you can understand what they’re saying. So which forms should you be learning by heart when you’re studying Finnish vocabulary? For nouns, the maximum number of different stems is four, and you can learn all of them by learning the following forms of any given word: Vesi ‘water’

Luckily, a whole lot of Finnish words just have one stem: you stick all the case endings at the end of the nominative and you’re good to go.

The difference between the genitive and essive is a regular phonological change called consonant gradation or kpt change. If we go back to water, veden has the weak version of the stem and vetenä has a strong version with a t instead of the weak d. I’m personally quite bad at consciously applying grammar rules as I speak, so my strategy is rather to learn the different stems by heart, but it might be easier for you to think of it as three possible versions of a word:

If you’re just starting to study Finnish, all this can seem daunting. If you have any perfectionist tendencies at all, you might feel like there’s a ton to learn before you can even string two words together. This is not true: you don’t need to know all the forms perfectly to understand and to make yourself understood. Mistakes are an unavoidable part of the journey when you’re learning any language, and with a language with like Finnish with lots of different word forms (in linguistic terms, languages with a rich morphology), they’re something to be learned little by little as you go, not something to be mastered completely here and now before you can progress to really expressing yourself. When in doubt, just stick the case ending on the perusmuoto and see what happens. It’s very likely to be the right form. It also might not be, but nothing dangerous is going to happen if it’s not. As you keep going and adding to your Finnish skills, you’ll start finding the right form more and more often. Hyvää uutta vuotta!

good-partitive new-partitive year-partitive = Happy New Year! (or, literally, good new year) If you’ve already studied Finnish for some time, you’ll know that Finnish words come in many, many different forms. For example, here’s the word vesi, water:

Vesi on kylmää. The water is cold. Veden lämpötila on 5 astetta. The water’s temperature is 5 degrees. Saisinko vettä? Could I have some water? Sade tulee lumena pohjoisessa Suomessa ja vetenä etelässä. The rain (sade = the precipitation) will fall as snow in the north of Finland and as water in the south. The word vesi has four different stems (or forms that case endings are added to):

Luckily, most Finnish words just have one or two different stems. Some have three, and just a handful of words have four, like vesi here. So when you come across a new Finnish word, how do you know what word it is and what form it’s in? The answer to this is that, unfortunately, you have to look the word up and learn the different forms of the word by heart. A superb tool for this is Kieli.net. Kieli.net is a simple online tool where you can enter any Finnish word in any form and get the perusmuoto (nominative for nouns, A-infinitive for verbs) and all other possible forms of that word as well. As with any online tool, take the results with a grain of salt (I’m looking at you, Google Translate). There are still sometimes mistakes and inaccuracies on Kieli.net, but all in all it’s quite accurate and pretty great overall! Luckily, there are also rules and regular patterns that help you. For example, each and every word ending in nen works the same way:

With words ending in the vowels o, u, ö and y just have two possible forms, the strong kpt version and the weak one

And so forth. As you practice all this and progress in your studies, you’ll find that you’ll start to autimatically recognize all the different forms and be able to use them intuitively. There are also rules and patterns to help you with this, so it’s not all just memorizing word after word! What tools have you used to figure out the different forms of Finnish words? Which ones would you recommend? A reader asks: Hi, how are you? I have a question. What do jo, vielä, vasta and enää mean? Can you write examples? Thank you very much and have a nice day! Here’s the original question in Finnish: Hei. Mitä kuuluu. Minulla on kysymys. Mitä tarkoitta jo viela vasta ja enää. Voitko sinä kirjoittaa esimerki lauset . Kiitos paljon. Hyvää päivää. Heippä Hei ja kiitos kysymyksesta, hi and thanks for the great question! Jo, vielä, vasta and enää are small words that many learners of Finnish struggle with. Let’s dive right in! To write this, I referred to the excellent Kielitoimiston sanakirja to make sure that I catch the most important uses of each word. By clicking on the word in question, you can go directly to Kielitoimiston sanakirja’s definition and examples. 1. Jo means that something has already happened: Tein kotitehtävät jo eilen. I already did the homework yesterday. Hän tykkäsi laulamisesta jo lapsena. She liked singing already as a child. Onko kello jo kolme? Is it three o’clock already? 2. Vielä expresses that something is still going on: Asutko vielä Helsingissä? Do you still live in Helsinki? Or that something hasn’t happened yet: Minulla ei ole vielä työpaikkaa. I don’t have a job yet. And as an expression of more: Haluan juoda vielä yhden kupin kahvia. I want to drink one more cup of coffee. With the comparative: Vanha kitarani on ihan hyvä, mutta uusi kitarani on vielä parempi. My old guitar is good, but my new guitar is even better. 3. Enää. In negative sentences, enää expresses that something isn’t happening any longer: En ole enää koulussa. I’m not at school any more. Ei enää koskaan! Never again! In positive sentences: Meillä on enää kaksi korvapuustia jäljellä. We only have two korvapuustis left. Enää 100 kilometriä! Only 100 kilometres to go! 4. Vasta can often be translated as just or only: Kello on vasta kaksi. It’s only two o’clock. Näin hänet vasta viime viikolla. I saw him just last week! Vasta also means the bunch of twigs that you hit yourself with in the sauna (also known as vihta), but I don't think you were asking about that vasta! Helsingissä lehdet ovat jo pudonneet puista. Lehdet eivät ole enää puissa. Vielä ei ole pakkasta. Vasta äsken oli kesä!

Picture by PublicDomainPicures A reader asks: Hey i heard that you shouldn't use you correct name, email or address when you are writing the yki test kirjoittaminen. for example if you are ending a letter and you write: Ystävällisin terveisin you should not use your real name after it... is that correct? I' My answer: The YKI test is really good about protecting their test takers' personal info, so if that's the part you're worried about I'd say not to worry, your personal info is safe. The people who see your writing and your name are teachers specifically trained for YKI assessment, and they've all signed an agreement not to share any of the info they come across, including your name if you've chose to share it. Your writing and speaking may also be used for training and research purposes. However, the thing to take into account with sharing your real name in the YKI test is that names always contain information about where you're from. We live in a racist world, and sharing your real name might affect the way your test is evaluated. I really wish this wasn't true, but I can't pretend that this never happens. I know many of the YKI test assessors personally, and I know that they are anti-racist people who work very hard to be as fair as possible, but unconscious bias and internalised racism are unfortunately very real even in people who make a conscious and constant effort to do better. The YKI criteria are quite good (though far from perfect) and the test has been studied extensively to make sure that it's as fair and objective as possible. I'd say that even in the worst case, racisim can only play a very small part in how your test is assessed. Still, any time people are involved there's all kinds of things that affect the process, including any predjudice that the assessor may have, so I can't honestly say that there's no risk of disadvantage here. If you decide to go the route of not using your real name, I'd suggest you think of the name you'll use well in advance, so you don't have to spend any of the precious time in the test on picking out a pseudonym. As it's a Finnish language test we're talking about, maybe something like Matti Meikäläinen or Maija Meikäläinen (the Finnish equivalents of John and Jane Doe), or a super common first and last name like Juha Virtanen or Laura Jokinen. This has the added benefit of showing off your knowledge about Finnish names, and can be fun, even if the reason for doing it is pretty bleak. TL, DR: It's small risk, but it's still real risk that's very easily avoided in a way that allows you to show off your knowledge of Finnish language and culture at the same time. Edited 6.10.2021 to remove some typos and to add: It should never be on you to change yourself or your identity for the comfort of others, so please don't feel like using a pseudonym is something you have to do if you don't want to. Names are important, and changing your name can feel like erasing your identity, and that's just not worth it for a language test. Edited 9.10.2021 to add: After reading this post, my YKI assessor friend pointed out that the test taker's real name is displayed on test more prominently than I had previously realised (as I don't assess YKI tests myself, I of course don't quite know the details are like). So it's probably not at all worth spending energy making up a pseudonym after all! Picture by Free Photos

1. Just listen. A key part of learning any language is getting used to how it sounds. What kind of music is Finnish? What syllables stand out to you? What is the melody and the rhythm of the language like? It doesn’t matter if you don’t understand a word of it, just listening to spoken Finnish is extremely beneficial. Our brains are masters of detecting and learning patterns, and your brain will automatically start trying to make sense of any language you expose it to. For most small children learning their first language or languages, this alone will eventually lead to speaking the language perfectly, but we adults need to do a lot more active work. However, we don’t lose that skill entirely when we grow up, and it’s good to take advantage of it! 2. Pay attention to prosodic features. Prosodic features are the musical properties of language, like melody and rhythm. Take any recording of spoken Finnish that you can replay over and over again, and intentionally listen for patterns. Where does the melody rise, and when does it fall? Usually, the key words of any given conversation stand out somehow – usually they’re spoken more loudly and clearly than the rest. 3. Practice pronunciation. I pay a lot of attention to pronuciation in my classes. The main reason for this is that I find that learning how to pronounce different sounds and prosodic patterns is by far the quickest and easiest way to learn how to recognize them when you hear them, which makes it easier to catch those key words and understand what’s going on. Of course pronouncing Finnish well is also helpful in making yourself understood, but there are many, many ways of pronouncing Finnish well. Your accent always reflects where you come from, and that should be celebrated, not erased. As long as you can distinguish between the different sounds and main prosodic features, you’re speaking well enough to be understood. For the purpose of practicing these sounds and patterns, it’s a good idea to mimic and exagerrate what you’re hearing so much that it feels like you’re making fun of the speaker that you’re modeling yourself after. 4. Listen to Finnish music. Music makes learning easier: grammar, vocabulary and idiomatic phrases are often much easier to remember if you’ve leart them from a song. Here’s a fun little website and app called Lyricstraining, where you listen to songs and fill in the missing lyrics. 5. Sing in Finnish. You don’t have to be a good singer to do this, and no one has to hear you do it! Singing will improve your listening comprehension in the same way that more general pronunciation practice will, but it will be much more effient thanks to the music involved! 6. Listen to authentic conversations or to materials that are authentic or sound as authentic as possible. Listening comprehension exercises in textbooks are great practice, but they often lack authenticity. If you live in Finland, listen to the conversations happening all around you. The list is endless: podcasts, the news, sitcoms (like Luottomies on Yle Areena), whatever feels most accessible to you where you are at the moment. Remember tip number 1: you don’t have to understand a single word! Yle Kielikoulu, the Kotisuomessa website and Gimara’s soundcloud are great places to look for authentic and authentic sounding materials to listen to. 7. Learn how spoken Finnish works. If you’ve studied Finnish for a while, you probably already know that Finnish is spoken very differently from how it’s written. This isn’t a question of formal versus informal either: like any language, spoken Finnish has a whole spectrum of registers from very formal to very informal. What we teachers often call “puhekieli” isn’t slang or lazy Finnish, it’s a spoken form of Finnish that is generally understood and spoken all over Finland, but heavily influenced by the local dialect spoken in the Helsinki area. The official term for this form of spoken Finnish is “yleispuhekieli”, sometimes Standard Spoken Finnish in English. Unlike written language, which has clearly defined norms and rules, spoken Finnish has lot of variation, and it’s a good idea to learn about different dialects as well as yleispuhekieli and written Finnish. Not an easy task for the learner, I know! Luckily though, it’s not really that different from written Finnish once you get the basics down, and there are materials to help you with this. This free online course will teach you the basics. 8. Get into those real-life situations! Yes, it’s possible that you won’t understand anything at all at first, but it will get so much easier as you build up more experience. Again, remember tip number one as you go about this! Real life, real time conversations have the great advantage that you can ask for clarification when you need it, and if you have another language in common with the other person, you can begin by replying with other languages as well as Finnish – it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. When I’m with my Norwegian friends, I often understand most of what’s going on right until someone asks me a question, of which I usually don’t understand a single word. I used to panic when this happened, but now I ask for the translation and reply in my own mix of scandinavian languages if I have the energy, or in English if I don’t. After that, they pick back up in Norwegian, and I’m learning loads! 9. Participate in conversation groups. If you’re not ready for real life situations (and even if you are) there are lots of fun, free conversation clubs, groups and language cafés that you can participate in. Some of them are already happening face to face all over Finland (and other countries as well!), and I’m pretty sure there will still be lots of online events to attend even after pandemic times. Listening to other learners speak helps you learn really efficiently, and can also feel safer than a conversation with native Finnish speakers. If you're in Finland, your local library probably has an ongoing conversation group for learners. I myself am a member of a non-profit organization called Mothers in Business, who have a lovely Language Café that I plan to attend again once things in my life (the terrible twos! two working parents!) settle down a bit. If you can’t find anything suitable, consider starting your own club, it’s really efficient and great fun. 10. Give yourself time. Every language learner knows that infuriating feeling: you know you’ve learnt a word or phrase before but can’t remember it. It gets even worse if you keep telling yourself that this should be easy. “I’ve been studying for so long, I shouldn’t be having trouble with this.” When you do this, all your energy and concentration is spent on this “shoulding” instead on listening. Again, easier said than done, but: when you stop shoulding all over yourself, and start approaching conversations with an open mind, understanding what’s going on gets so much easier. If you've been studying Finnish for quite a while now but still struggle to understand what's going on around you, my upcoming course Puhetta! for levels B1 and B2 might be just the thing. Check it out here! Picture by SplitShire

|

Archives

June 2024

|

Ask a Finnish Teacher / Toiminimi Mari NikonenBUSINESS ID (Y-Tunnus) 2930787-4 VAT NUMBER FI29307874 Kaupintie 11 B 00440 Helsinki If you'd like to send me something in the mail, please email me for my postal address. [email protected] +358 40 554 29 55 Tietosuojaseloste - Privacy policy |

© COPYRIGHT 2015-2022 Mari nikonen. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed