|

Reader Karen made a great suggestion in the comments of How to practice speaking when studying on your own.

Karen writes: My speaking is at a basic level and most finnish people are not accustomed to adjusting thier speach to someone learning the language so english is just easier :( Actually it may be very helpful if you can write a blog aimed at friends and partners of thoes learning finnish and how they can help us! English speaking Finns love to practice their English, which I suppose is a good thing in many ways. However, it's not such a great thing when you're trying to learn Finnish - how do you learn a language if you never get to practice? Many Finns think that speaking English is always the considerate thing to do, but never stop to think that it's actually massively impolite to speak English to someone who's doing their best to speak Finnish. How would they feel if they tried speaking Spanish in Madrid after studying for a year (or a week, or even an hour) only to get an answer in English? It sometimes amazes me that we're still grappling with this problem in 2018, but here we are. Finns are still very intolerant of non-native variations of their language, and lots of my students who actually speak better Finnish than English find themselves having to constantly resort to English in everyday situations to make themselves understood. Of course, not everyone speaks any English at all, so this "helpful" tendency to speak English can become very confusing very quickly. It of course gets worse if you don't look or behave in a stereotypically Finnish, so much so that many native Finnish speakers have trouble with people constantly speaking English to them. This of course something that needs to change, but it's also something that a language learner doesn't necessarily have a lot of power over. So what can you do to help your Finnish friends and family help you learn Finnish? Lots of people have written excellent texts on this subject in Finnish, so point your near and dear Finns in the right direction. I recommend this text from Maisa Martin. It was written 10 years ago but things unfortunately haven't changed that much from 2008. For practical suggestions that any native speaker can use to help learners learn, have them check out Suomen kieli sanoo tervetuloa. It is geared towards native Finnish speakers who want to volunteer as Finnish teachers, but the method and suggestions are very practical and I think very useful for starting to speak more Finnish with family members as well. Speaking your native language with a non-native speaker is a skill like any other skill. It's quickly learned but it does take a bit of practice and lots of patience from everyone involved. I know all too well that it can a lot feel easier to just speak English, but the benefits of practicing with a native speaker are very much worth the effort. There's also no need to switch to speaking Finnish 100 % of the time. Like with any new thing, it's a good idea to start small - for instance, you could suggest to your Finnish speaking loved ones that you spend just 5 minutes a day speaking only Finnish together. You could try that for a week and see how that feels, then see if you want to keep doing that, or maybe even up the challenge to 10 minutes a day. Or to a half a hour twice a week, or whatever suits your schedules and needs best. My parents live in Oslo, so I've been speaking Swedish peppered Norwegian words in Norway for many years now. In my experience Norwegians really excel at speaking Norwegian to foreigners - they all seem to automatically repeat everything several times to make sure I understood, and if I need to ask something in English they'll go right back to speaking Norwegian afterwards. I'm often thinking of my Norwegian friends when I'm speaking to my students and try to do what they do. Maybe we Finns need a Norwegian or two to teach us how? As a native Finnish speaker, I obviously don't have much first hand experience with getting Finns to speak Finnish with me. If you do, please share your experiences in the comments, I'd love to hear about them! Gennady asks: How to practice speaking and spoken Finnish when you're studying Finnish on your own? This is a timely question for me, as I've only recently started spending more time in online groups for people who are studying Finnish. I've been amazed and touched by how many people all around the world are studying Finnish all on their own, often completely dependent on the free material available online. Studying any language on your own is difficult, and Finnish is definitely a challenging language in many ways. So my first piece of advice would be to find a course or private teacher if at all possible for you. There's a growing number of people teaching Finnish online (me included!), which can be helpful if there are no Finnish classes in your area. So, on to the question! If you're studying on your own, how can you practice speaking and spoken language? Listen as much as possible. Listening and speaking are inextricably connected. The more you listen to Finnish, the easier you'll find it to speak Finnish yourself. There are listening comprehension exercises for every level that are freely available online, but I think it's important to listen to all kinds of things in Finnish from the very beginning. Watch a movie or tv series in Finnish with or without subtitles. Listen to Finnish music. Listen to a radio program in Finnish. Even if you don't understand a thing, just getting a good feel for what the language sounds like helps so much. Find a tandem partner. This is one of my favourite ways to study a language. Find a Finnish speaker who wants to learn a language that you speak well. Then meet up with them regularly either face to face or online. Spend half of your meetings speaking Finnish and the other half speaking your language. Free, effective and so much fun! Talk to yourself. Stand in front of a mirror and say things in Finnish. If there's a new word or phrase that you want to learn, say it out loud, on your own, many many times. Make up a melody to go with the words or phrases. Get it stuck in your head. Record yourself. Have some recorded Finnish at hand and repeat after it, mimicing the original version as closely as possible. Record yourself and compare your speech to the original version. Also, check out Dublearn. Dublearn is a free app that you can use to dub videos in different languages. Then you can compare your version with the original version and get feedback on your version from other dublearners. Amazingly effective silly fun! Try to think in Finnish. Once in a while, try to switch your brain to Finnish. Even if it's just for a few minutes at a time. Focus on trying to think in Finnish, and when you inevitably find yourself thinking in another language, gently direct yourself back to Finnish. You could even use a meditation timer to keep yourself focused. Make up your own dialogues. Think up conversations in Finnish, maybe even write them down like a script for a play. Get a friend or family member to practice them with you. Sing in Finnish. There's a growing body of research that tells us that singing and music in general are really effective ways of learning a language. So go find a Finnish song that you like and learn it. If you can't sing, sing anyway - the point is learning Finnish, not wowing an audience. What are your favourite ways of learning to speak? Picture by 6689062

Finnish classes have a tendency of being very grammar heavy. This is in part because of how the language itself works, but it's also just plain tradition. Grammar rules have played a central part in language learning at least for hundreds, maybe even thousands of years, going at least back to how Greek and Latin have been studied throughout the centuries. Grammar can mean many things, from a set of rules to follow to theories about language to being synonymous with the structure of language itself, encompassing every aspect of language use: phonetics, vocabulary, genres, contexts and so on. For the purposes of this post, I'll be using the word grammar to mean the set of rules that you learn and practice when you're first learning a language - in linguistic terms, phonology, morphology and syntax. For instance, the word type rules in my previous post and exercises to practice them would be an example of what I mean by grammar. One of the reasons why Finnish is difficult is that there's often a lot of emphasis placed on getting the forms right right away, by us teachers but also by students. I help moderate a language learning group on Facebook (Learn Finnish Language - Opiskelemme suomea, you're very welcome to join us), and a lot of the discussion centers around people asking if the sentences they have written are correct. This is of course a good thing - it's fine to want to get your grammar right from the beginning, but a lot of the time it can become an obstacle on the way to actually learning to understand, speak and write Finnish. The problem is that with a language like Finnish, where there's a lot of morphology (word forms, cases, tenses...) to learn, there's nearly always a little something wrong with even the most meticulously crafted sentences. That, in turn, makes you lose confidence in yourself and your ability to learn, and learning Finnish starts to feel like an impossible task. The truth is, usually you can get the message through without getting everything right. I if writes like zis, you understandings I, yes? The same of course goes for Finnish. When I'm studying a new language, I find myself terrified that if learn the forms wrong in the first place, I'll never ever get them right. However, that is not at all what I've seen as a teacher, or what the research tells me. It's absolutely possible to learn the language wrong and to then have a hard time unlearning the errors and relearning the correct forms, but in my experience this is actually quite rare. I've never seen it be a problem for the students who keep an open mind and try their best keep learning even after the initial stage. What is true for 99,99 % of my students is that as they get more experience with the language, the correct forms also emerge, bit by bit. Then there's the 0,01 % who can read a grammar from cover to cover, then read a dictionary from cover to cover and start speaking more or less perfectly. Yes, those people exist (though the numbers are off the top of my head). As a talented language learner I have them to thank for knowing what it's like to be the slowest learner in class, which I think has made me a much better teacher. As a teacher, I'm often torn on whether to correct my students' mistakes or not. On one hand, speaking and writing the language and making yourself understood with it is what counts. On the other, I feel it's my job to help my students eventually get the forms right. What do you think, how much correction is the right amount? Here's what Helsinki looked like this morning. Stadi <3

Photo: Lena Salmen arkisto I got my first reader question! Not via the question form yet, but in the comments of Is Finnish Difficult. I'll take it!

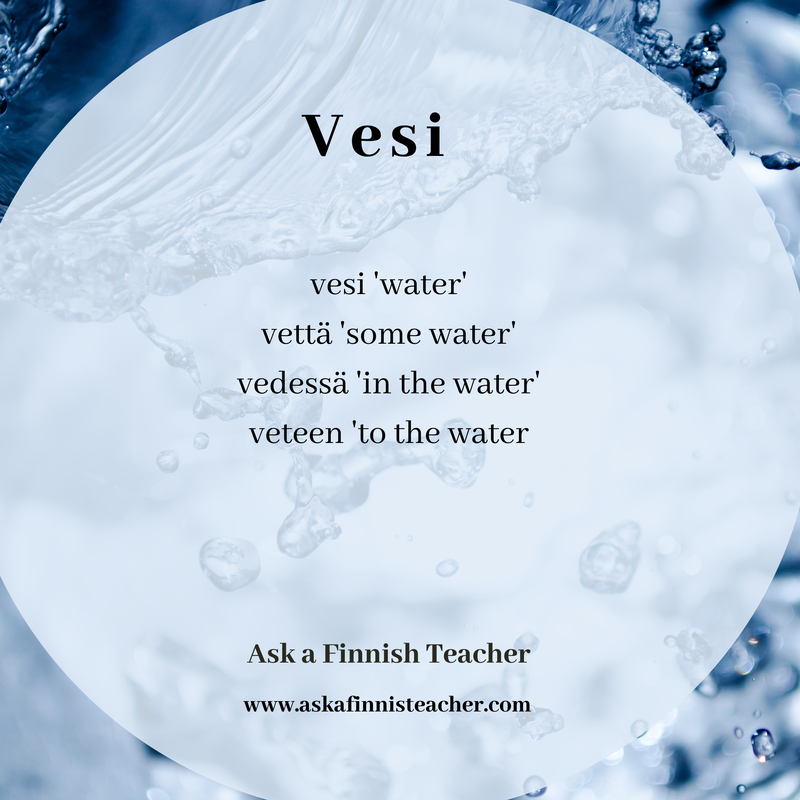

Feik asks: How do I know which Finnish i-word is "new" and which "old"? kieli: kielen vs tiimi: tiimin? From your question, I can tell that you know a lot of Finnish already, hyvä sinä! I'm going to start from the beginning for the readers who don't, so please bear with me. Finnish has fifteen cases, which are little bits of sound that we stick at the end of words to express things like where something is situated. English, for example, expresses these same ideas with prepositions (which, by the way, there are also a lot of and it can be really hard to know which one to use). So in English, you'd say for instance that someone is in the garden. In Finnish, that would be puutarha + ssa garden + in Not too hard, right? As a bonus, no pesky article to decide on. For a lot of Finns, it's mind bogglingly hard to know if they should say that they're in a garden or in the garden this time. I don't know where English gets it's reputation for being easy to learn. However, here comes the hard part: a lot of Finnish words change when you stick a case marker on them. For instance, all words ending in nen do this: suomalainen puutarha Finnish garden suomalaise + ssa puutarha + ssa Finnish + in puutarha + in suomalaisessa puutarhassa in a/the Finnish garden Whenever a word ends in nen , the nen becomes se: suomalainen 'Finnish' -> suomalaisessa 'in the Finnish' iloinen 'happy' -> iloisessa 'in the happy' Nikonen 'the teacher's last name' Nikosessa 'in the Nikonen' The really hard part is, you can't always tell which word group a word belongs to just by looking at it, and this is where we get to you the question of the day, new and old words ending in i. When a word ends in i, there are four word groups it might belong to: 1. HOTELLI-words These are the new words that Feik is referring to. In this word group, the endings are just stuck on and nothing strange happens. These words are relatively new loan words, and if you speak English or Spanish for example, you'll recognize a lot of them straight away. bussi -> bussissa tomaatti -> tomaatissa normaali -> normaalissa Maybe you can guess what those words mean. 2. SUURI-words In these words, the i at the end transforms into an e before the endings. suuri 'big', i -> e -> suure + ssa 'big + in' = suuressa 'in the big' kieli 'language' i -> e -> kiele + ssä 'language + in' = kielessä 'in the language' You might have noticed ssä for in. Yeah, we have two versions of in, ssa and ssä. Also, SUURI-words are irregular in the partitive case (which literally means a part of something): suuri 'big' suurta 'a part of a big' kieli 'language' kieltä 'a part of a language' 3. LEHTI-words As with SUURI-words, the i becomes an e before the ending. Also, there may be a kpt-change, but that deserves it's own post or three. lehti 'newspaper' t -> d, i -> e lehde + ssä 'newspaper + in' lehdessä ' in the newspaper' LEHTI-words are only different from SUURI-words because the partitive is regular. lehti ' newspaper' lehti + ä 'newspaper + a part of a' lehteä 'a part of a newspaper 4. VESI-words This word group is a group of very old words, from the time where all we had out here was water, our hands, some wolves and years and years of time. vesi 'water' vede+ssä 'water + in' = vedessä 'in the water vettä ' some water' (the partitive, so more literally, 'a part of water') When you come across a new Finnish word ending in i, look it up and see which group it belongs to. A good tool for this is the free online Finnish dictionary Kielitoimiston sanakirja , which is a great quality dictionary carefully refined by language professionals for decades and updated regularly. There are some clues, of course. If it sounds familiar from English, French, Latin, German, Russian, Swedish etc, it's probably a HOTELLI-word. If it's something that's always been around in Finland, it's probably one of the other three. If it ends in si, it's probably a VESI-word.* But there's really no other option than just memorizing, I'm afraid. *I edited this part a bit after some comments from a kind colleague, it originally read: If it ends in si and is something that has always been around in Finland, like susi 'wolf' or käsi 'hand', it's probably a VESI-word. One of the questions that I get asked most often is this one. Sure, Finnish is difficult to learn. Learning any language from scratch is difficult, and Finnish grammar is notoriously complex, with 15 cases that may or may not look totally different in their singular and plural forms. So yeah, it's difficult.

The level of difficulty you're likely to face depends on a couple of factors. 1. What you're comparing it to. There are approximately 7000 languages spoken in the world today (it depends on how you count), and I can guarantee you that Finnish is not the most difficult one. 2. What languages you already speak. If you're already fluent in Estonian, you'll learn Finnish pretty quickly. The big Indo-European languages like English, French, German and Russian are all related, and so they share a lot of grammar and vocabulary. Finnish and Estonian are from an entirely different family of languages, the Finno-Ugric languages. However, Finnish has a lot of loan words from its Indo-European neighbors, so it helps if you know one or more of them. 3. How many languages you already speak. People tend to think that there's only so much room in our brains for languages, as if our brains are bookshelves, and small ones at that. Or memory sticks with exactly one gigabit of storage space, and when it's full it's full, so you must choose carefully. That's not how learning works. The more languages you know - any languages, no matter how much or little you know - the easier it gets to learn a new language. If you're an adult who only speaks one language, English, for example, you'll have to work a lot harder than someone who's bilingual from childhood and has already studied several foreign languages. But if you only speak one language, fear not! I've seen many, many people in your position learn Finnish and you can, too. But you have to want it. 4. How motivated you are. Learning any new language well is a huge goal and takes a lot of time to reach, and you need to really commit to get there. It helps a lot if you have a concrete reason to want to learn - maybe you live in Finland, or have a Finnish family member. Or maybe you want to spend a holiday in Finland and be able to order your korvapuusti in Finnish. 5. How much of a perfectionist you are. To learn any new language from the very beginning you have to be willing to make a lot of mistakes and continuously make a fool of yourself for a very long time. Perfectionism is the enemy of learning anything, but it becomes a huge problem with a language that inspires memes like this: I teach Finnish to adults in Helsinki. For the most part, I speak to my students in Finnish. Even the beginners.

In my day to day life, I get asked so many questions that I don't really get to answer, and I'm sure that there are many questions that simply don't get asked. I've created this blog to make it easier to ask, and to make it easier to answer. I've decided to write this blog in English, but you can write to me in French, Spanish, Swedish, Estonian and of course in Finnish. |

Archives

June 2024

|

Ask a Finnish Teacher / Toiminimi Mari NikonenBUSINESS ID (Y-Tunnus) 2930787-4 VAT NUMBER FI29307874 Kaupintie 11 B 00440 Helsinki If you'd like to send me something in the mail, please email me for my postal address. [email protected] +358 40 554 29 55 Tietosuojaseloste - Privacy policy |

© COPYRIGHT 2015-2022 Mari nikonen. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed